-

Ramadan traditions in Egypt: lanterns, cannons and night callers

Ramadan has many rich traditions which support Muslims in their fasting, developed over many centuries. They evoke a very special spiritual time, and will often trigger nostalgia and emotion.

Feeling part of a bigger context

The core of Ramadan is its religious obligation: to avoid all physical intake during daylight hours. It’s worth looking at the verses of the Qur’an as a framework to understand the clear significance of the month for Muslims, and how they feel it places them within a larger historical narrative about the importance of this gruelling yet uplifting ritual: “O you who believe! Fasting is prescribed for you as it was prescribed to those before you, so that you may become conscious of God.” [Chapter 2, verse 183]. What you can take away from this is an insight into why fasting gives Muslims a sense of being part of something bigger than themselves, that has historical and social context.

Of course, alongside the religious stipulations, a rich fabric of traditions and social mores have arisen which – literally – bring colour, culture and life to communities. These vary across the world and often date back centuries. In this post, we’re going to look at Egypt, where many of the Ramadan traditions date back to the Fatimid era.

Egypt has a fantastically rich Ramadan heritage, ranging from lights to cannons to night callers.

The Ramadan lantern

The ‘Fanous’ of Ramadan is one of the most captivating of the Ramadan traditions. It is said that Egyptians welcomed the arrival of Caliph Moezz Eddin Allah to Cairo in 969 by lighting hundreds of lanterns. Since that time, the fanous has been a staple of the many traditions that characterize the Holy month of Ramadan.

According to some tales the Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi Amr Al-Lāh, who wanted the streets of Cairo illuminated during the nights of Ramadan. He ordered all the mosques to hang fawanees (lanterns) that could be lit by candles. Another account tells of the Fatimid Caliph’s going out into to the streets to sight the crescent moon of Ramadan, accompanied by children holding fawanees and sing Ramadan songs.

In other folklore, Caliph al-Hakim (996-1021) also of the Fatimid dynasty was said to have ordered that women were only permitted to leave their home at night if they were accompanied by a boy carrying a lantern, and also that every neighbourhood should have a lantern hung at its entrance. Not surprisingly, the lantern industry went through a boom.

Today it’s children who are usually associated with going out into the streets with their beautiful and brightly coloured lanterns. There is, however, a worry that traditional lantern making is being lost to imports and that Egyptian artisanship which is showcased during Ramadan in particular will be lost.

Firing the cannon

The firing of a cannon, sometimes known as ‘Haja Fatemah’, marks sunrise and sunset, and

therefore signals the time for beginning and ending the fast. Although an Egyptian custom by origin, it has now spread to other countries.When the Mamluk Sultan Al-Zaher Seif Al-Din Zenki Khashqodom received a cannon from a German acquaintance, his soldiers tested it by firing it at sunset, which happened to be in Ramadan and so co-incided with the time for breaking fast. The inhabitants of Cairo thought the Sultan was alerting them to the time for iftar. Realising that such a custom could increase the popularity of the Sultan, dignitaries suggested to him that he should continue the practice.

It is said the Sultan’s wife Haja Fatemah received them when they came to deliver their suggestion as the Sultan was not home, and so the cannon is now named after her.

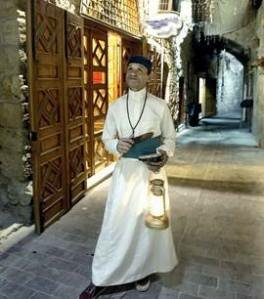

Al Mesarahaty

Finally, another tradition is the Al-Mesarahaty, the Night Caller. He takes the task of walking around the village or city waking people in time for suhoor, the meal taken just before dawn. In some small villages he may even stand in front of each home and call each inhabitant by their name in order to wake them. In larger places he may stand on each street and bang his drum to wake people. One of his traditional songs is “ Suhur, suhur / Es ha ya nayem/ Wahed el dayem/Ramadan Kareem/ Es ha ya nayem, wahed el Razzaq” which translates loosely as “Wake up you who are sleeping, pray for eternity, Happy Ramadan, God is the One who sends you your sustenance”. The Mesarahaty does not take any payment for this night-time work, but it is customary at the end of Ramadan to give money or a gift for his strenuous efforts.

Al Mesaharaty [image from relijournal

Time change

A much newer twist Egypt’s Ramadan was in 2010 when the government halted Daylight Savings Time (DST) and put the clocks back one hour to make the time for breaking fast earlier. (although this doesn’t make the fast shorter, of course.) This likely eased fasting for the population, but also minimised the impact on economic productivity that fasting can have. Subsequently, a poll was held to see if DST should be abolished altogether, which was passed, and now iftar time remains the one hour earlier, and there is no changing of clocks backwards and forwards.